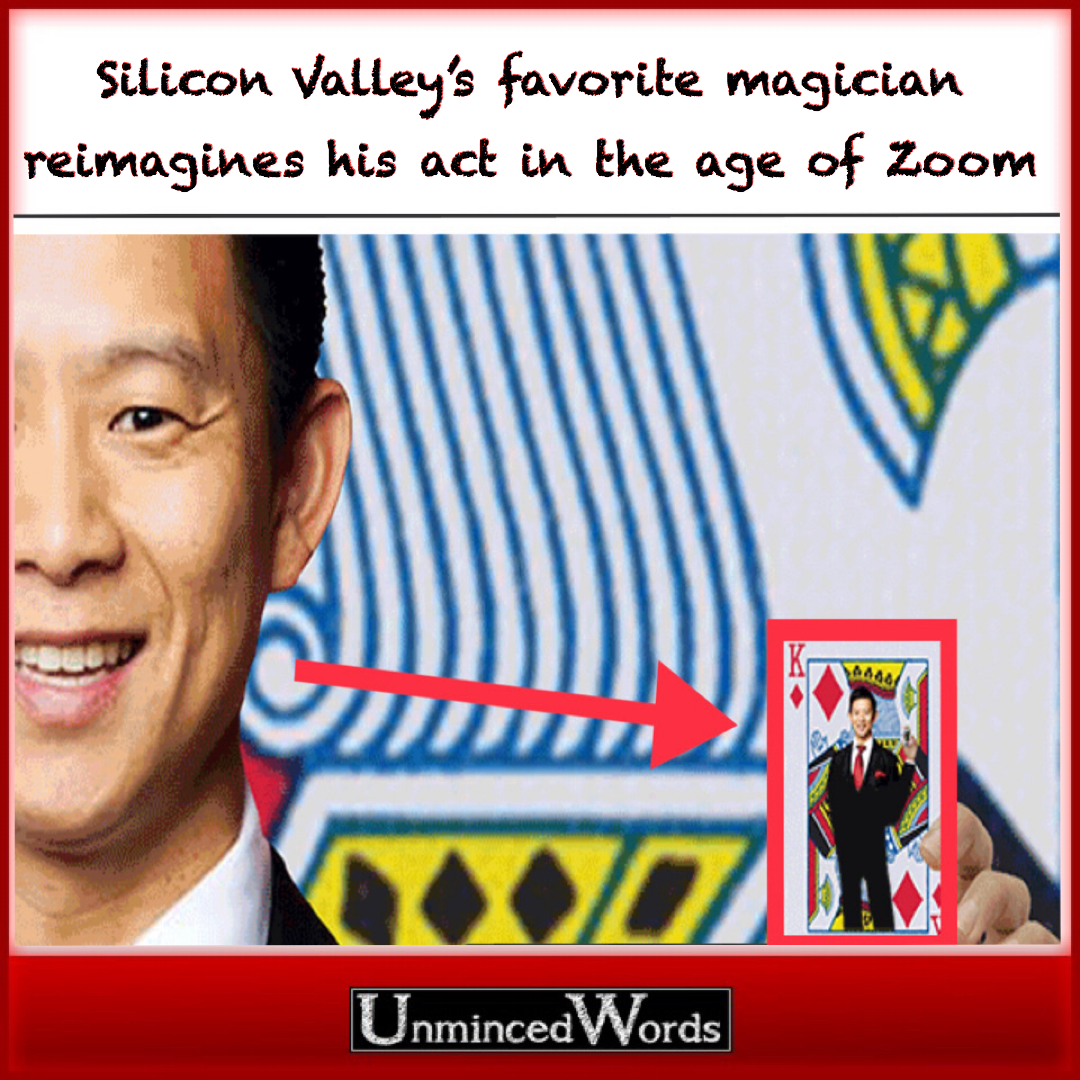

Silicon Valley’s favorite magician reimagines his act in the age of Zoom

Daniel Chan has stumped billionaires, CEOs, and engineers with his technology-driven tricks. Now, technology is changing the nature of his show.

On a recent Thursday night, Daniel Chan — one of Silicon Valley’s top corporate magicians — was Zoombombed during a test run of his online show.

As Chan’s 12-year-old son juggled for a dozen remote guests, an intruder took control of the screen, streamed porn, and assaulted the room with racial slurs. By the time Chan managed to boot him out, all but one audience member had left.

“I’m still working out these online shows,” he ceded while shuffling a deck of cards. “If that were a paid gig, it would have been a disaster.”

In the course of his 20-year career as a professional magician, Chan, 42, has performed more than 5k shows for technology giants like Google, Twitter, and Apple. He’s stumped top engineers with iPhone tricks, juggled fire in the backyards of palatial mansions, and dazzled billionaires with his sleight-of-hand illusions.

But now, with offices closed and most in-person gatherings prohibited, he’s had to pivot to a virtual stage — and, in the process, re-tailor his approach to magic.

Magic as escapism

Growing up in San Francisco’s Richmond District, Chan was often the target of bullying. The neighborhood kids called him “monkey” because his ears stuck out. Once, someone gave him a black eye.

“I didn’t have any social skills,” he says. “So, I decided to get really buff and study magic.”

Chan in his youth, at a San Francisco playground (Courtesy of Daniel Chan)

Chan can’t remember his first encounter with magic, but he’d been enthralled by magicians at birthday parties and theme parks. Their illusions offered an escape from reality.

During high school, he dabbled in card techniques, perfecting the one-handed cut and the hand-to-hand spring. Later, while studying business administration at UC Riverside, he locked in with the campus juggling club and started to read magic literature.

After graduating in 2000, Chan was hired at the then-fledgling PayPal, as a $32k-per-year customer service rep. For a time, magic took a backseat to payment processing. But 13 months into his tenure, Chan was laid off.

So, he decided to become a full-time magician

Back in San Francisco, Chan really began to dig in and study magic — both as a craft and a business model.

He conducted a SWOT analysis to determine his own personal strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, and analyzed the magic landscape using Porter’s 5 Forces:

1. Competition in the industry

2. Potential of new entrants into the industry

3. Power of suppliers

4. Power of customers

5. Threat of substitute products

Chan started hanging out at Misdirections Magic Shop, mapping out his competition and gathering intel from the local professionals. The going rate for a private show, he learned, was anywhere from $250 to $1.5k.

“I reverse-engineered the math,” says Chan: “$250 per show multiplied by 200 shows a year — that’s $50k per year, a lot more than I made at PayPal.”

There was just one problem: The corporate market was cornered by more established magicians with deeper connections; Chan was green.

To cut his teeth, he broke into the school and library magic market. Though he wasn’t the most talented magician at that point, his breadth — magic, juggling, tricks with live doves — earned him 50 gigs per summer.

Over the next few years, Chan performed hundreds of these shows. And soon, he began to attract the attention of a different demographic: Tech millionaires.

“Everyone in Silicon Valley talks,” he says. “People who’d seen me at a library started recommending me for birthday parties. They didn’t want some old clown; they wanted a young guy who juggled fire.”

Chan soon found himself in the backyard of a $45m Los Altos mansion, entertaining the children of a wealthy tech executive.

In the mid-2000s, the Valley was teeming with VC money and big exits. Over-the-top birthday bashes were common: Chan recalls a $250k Harry Potter-themed party thrown for the child of an early Google employee. Another parent spent $10k to fly in a Mickey Mouse actor from Disneyland.

For his services, Chan often cleared $500 to $1k per party. But he realized that the real money was in the pockets of the corporations employing the party guests.

“Other magicians would leave the party after an hour,” says Chan. “I’d stick around, have some caviar, and entertain the grown-ups, making signed dollar bills appear under their $50k watches.”

The billionaire’s magician

Through his party schmoozing, Chan was soon booked to do corporate gigs for the likes of Softbank, Intel, eBay, Apple, Google, and Twitter.

“I’d source a detailed product roadmap for them,” says Chan. “I’d take them through what my performances would look like 5 or 10 times down the road. I wanted to build long-term relationships.”

To appeal to his new clientele, he set out to rebrand himself as a corporate magician — not just an entertainer, but a marketing solution.

“When all my competitors were practicing magic, I was learning SEO,” he says. “I studied how guys like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs created these monopolies. I read Principles by [hedge fund manager] Ray Dalio. I tried to understand their world.”

Following a 2016 BuzzFeed story on his act, Chan rebranded himself from the kid-friendly “Dan Chan the Magic Man” to “The Billionaire’s Magician.”

He also perfected a new arsenal of technology-based tricks — many using an iPhone — that he thought would appeal to engineers.

For one trick, he’d source an iPhone from someone in the crowd and ask the person to think of any city in the world. Chan would then type something into the phone, set it face down, and tell the person to name the city aloud. When the guest retrieved his phone, he’d find the name of the city in a Google search on the screen.

Though many of his clients have made him sign non-disclosure agreements, Chan says he’s performed for some of the biggest names in tech. He’s done magic at black-tie parties, private banquets, trade shows, and the billionaire-laden Sun Valley conference.

Some have hired Chan multiple times, largely thanks to his aggressive tactics.

“I buy one share of stock in every company that hires me,” he says. “When their stock price goes really high, I send a follow-up email: ‘Hey, you guys are doing well! Seems like a good year to throw another party and hire a magician…’”

The economics of magic

For Silicon Valley parties that feature things like live crocodiles, 1,000-pound pumpkins, dinosaur fossils, and $20k ice sculptures, a magician is a palatable expense.

Chan generally charges $1k to $5k, depending on the venue and show format — a fraction of the $100k one of his clients reportedly spent to book the celebrity magician, David Blaine.

If a client can’t manage Chan’s fee, he offers up the services of his protége: His 12-year-old son, “James the Juggler.” James, who has been practicing magic from the age of 4, now commands between $250 and $750 per show. Someday, Chan plans to pass over the reins to him.

“My wife gets angry and says, ‘Maybe James wants to be something better than a magician,’” says Chan. “But he is learning the value of job security.”

Chan’s corporate gigs have placed him in a rarefied class of six-figure artisans: Last year, his performances netted him $160k in income.

But the craft doesn’t come without its overhead costs. In the last few decades, Chan estimates he’s spent upwards of $100k on magic books, DVDs, apps, and tricks purchased from magic consultants.

“There’s a lot of R&D in magic,” he says. “I buy a lot of things just to see how they work but never end up using them.”

His Bay Area home is littered with the whimsical tools of the trade: A gimmick gumball machine, a tip-over trunk, levitation gear, hundreds of card decks, and a $5k piano that can be played with bouncing balls.

But in recent times, Chan has had to rethink the entire physical nature of his show.

In the COVID-19 landscape, the “unknown” is a universal enemy. The world doesn’t want mystery: It wants explanations, answers, scientifically-validated truths.

Where does that leave magic?

The rise of the video conference magician

On March 20, shortly after California Governor Gavin Newsom announced a statewide lockdown, Chan lost $8k worth of bookings in the span of a few hours.

Like other entertainers — comedians, musicians, playwrights, and puppeteers — he pivoted to video shows on Zoom and Facebook Live. At $100 to $200 per show, the digital performances are a far cry from his usual rates but offer a greater reach.

“The first few Zoom shows were rough. I felt uncomfortable and awkward, and everything about my art seemed new again,” he says. “But I’ve realized that it’s the most scalable thing ever. I can reach people from all over the globe.”

Once relegated to ultra-exclusive settings, Chan’s tricks have been democratized by Zoom. He recently booked a virtual birthday party, a Google event, and a show on Twitch for San Diego State students.

“Someone is going to figure out this video stuff and kick it out of the water,” he says. “Someone, somewhere, is going to become the next David Blaine on Zoom.”

Chan isn’t the only magician trying to do that.

After his 35-city magic tour was canceled due to COVID-19, Alex Ramón decided to put on 35 Zoom shows in 35 days, live from his living room. Jon Finch, of Indianapolis, promises a show full of “inexplicable Zoom mentalism and strong Zoom magic.” Some charge on a “pay what you can” scale; others are choosing to perform for free.

But not everyone is bullish on the new medium.

Joshua Seth, a Florida-based magician who has performed live in more than 40 countries around the world, retired from magic when COVID-19 hit.

“It takes years to develop an act to the point where it will engage an audience,” he wrote. “Why squander that on a poorly executed online version that will redefine people’s perception of what you do and how well you do it?”

Performing on Zoom presents some challenges. For starters, there are attendance caps and occasional latency issues. Then, there are Zoombombers, who dip in uninvited on video calls. But the biggest hurdle for Chan has been figuring out how to reimagine magic — a craft built on physical interaction and trust — with the intermediary of technology.

“Re-envisioning your business won’t work like magic, but it will work if you have the courage to throw yourself into it. During this crisis, that’s what every entrepreneur who wants to succeed will have to do.”

Over time, magicians have successfully pivoted from stage to radio, to television, to the internet. Chan insists that the essence of magic transcends the medium.

Look into Houdini’s eyes… (via Getty images; edited by The Hustle)

To prove his point, he performed a trick for me over the phone, using email — a technology with more performative limitations than a video chat.

A high-resolution black-and-white photograph of Harry Houdini appeared in my inbox, and Chan asked me to name any playing card aloud. I chose the 7 of hearts.

“Okay, now screenshot the photo,” he instructed. “Open it on your desktop and zoom into his eyes.”

I zoomed in to find a “7” and a “❤” nestled inside of Houdini’s pupils.

“That’s incredible,” I said. “How’d you do it?”

“Magic.”

Zachary Crockett

Senior Writer, The Hustle

#magic #magician #zoom www.UnmincedWords.com makes #dreams come #true. Find a #gift in r #store & #buy it. It will #magically #arrive www.UnmincedWords.com #invites #you in on the #secret #tricks